Special Needs Trusts and Divorce / Part 2: Child Support

(On December 1, 2016, I moderated the first Advanced Special Needs Trust Symposium, an all-day event held at the New Jersey Law Center. In addition to moderating the panel of speakers, I also presented on the topic of the “Uses of Special Needs Trusts in Cases Involving Divorce.” Due to the length of my paper, I divided it into two parts. The first section, on Alimony and Property Settlement Agreements, was posted in a prior blog post, here. The second section of my paper, discussing child support, is posted below. It’s a complicated topic, and I hope readers find the paper useful in understanding the topic.)

CHILD SUPPORT

Sometimes a divorce is initiated as a tool for public benefits planning, where an ill spouse is facing the prospect of long-term care: not only can divorce be an avenue for the ill spouse to establish eligibility for Medicaid or other public benefits; it will also extinguish the well spouse’s responsibility to pay for the “necessaries” of the ill spouse, including the ill spouse’s nursing home care.

Other times, a more traditional divorce is initiated because of marital discord, but because there is a disabled spouse or child involved, special needs planning is impacted.

In either case, special needs trusts (“SNTs”) may be a critical component of the divorce.

Child Support

The general treatment of child support payments is outlined in Social Security POMS §SI 00830.420. According to that POMS section, child support payments made on behalf of an SSI minor child are unearned income to the child, with a one-third income disregard for an eligible child by an absent (non-custodial) parent. Current child support that is received for an adult child is income to the adult child, and is not subject to the one-third income disregard.

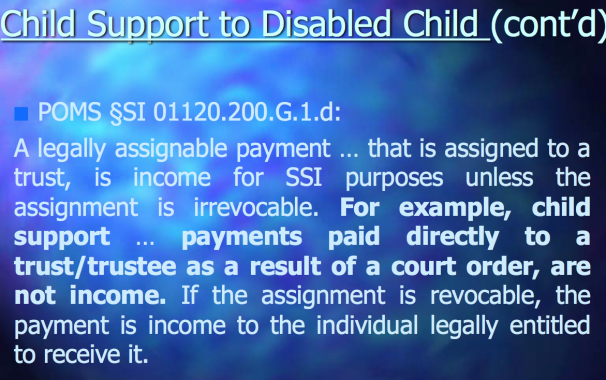

However, the Social Security POMS recognizes an exception to this rule for the irrevocable assignment of child support payments to a special needs trust:

A legally assignable payment … that is assigned to a trust/trustee, is income for SSI purposes unless the assignment is irrevocable. For example, child support … payments paid directly to a trust/trustee as a result of a court order, are not income. If the assignment is revocable, the payment is income to the individual legally entitled to receive it.

POMS §SI 01120.200.G.1.d. (emphasis supplied).

A central issue involved in the assignment of child support payments is whether the special needs trust must be self-settled (with a payback provision) or may be third-party (with no payback provision). If characterized as “child support,” certain protections, such as enforcement of payments through the probation department, are available. However, “child support” payments belong to the child. Because the child has a legal right to receive child support, many practitioners opine that the special needs trust that is created must be a self-settled trust, and payback provisions must be included. Mazart, G. and Spielberg, R., Trusts for the Benefit of Disabled Persons: Understanding the Differences Between Special Needs Trusts and Supplemental Benefits Trusts, New Jersey Lawyer Magazine, No. 256, February 2009.

The POMS section addressing self-settled special needs trusts includes the following example:

A disabled SSI recipient over age 18 receives child support which is assigned by court order directly into the trust. Since the child support is the SSI recipient’s income, the recipient is the grantor of the trust and the trust is a resource, unless it meets an exception in SSI 01120.203 [the self-settled special needs trust exception]. If the trust meets an exception and is not a resource, the child support is income, unless it is irrevocably assigned to the trust or trustee, per SI 01120.201J.1.d in this section. In this example, the court ordered the child support to be paid directly into the trust, so we consider it to be irrevocably assigned to the trust/trustee.

POMS § SI 01120.201.C.2.b.

As an alternative, some practitioners recommend that, if a divorcing couple agrees to forego protections such as the enforcement rights that come with payments of “child support,” the couple may enter into a settlement that does not include “child support,” but instead obligates the parent to make payments to a third-party special needs trust on behalf of the disabled child, as part of a property settlement agreement. Although the parent’s obligation to make these payments would not be the subject of child support enforcement protections, the obligation can be enforced as a contract right under the property settlement agreement. A more conservative approach would involve voluntary payments of income by the parent to a third-party SNT, separate from and in addition to court-ordered child support. Mazart, G. and Spielberg, R., supra, Trusts for the Benefit of Disabled Persons: Understanding the Differences Between Special Needs Trusts and Supplemental Benefits Trusts, New Jersey Lawyer Magazine, No. 256, February 2009.

Even if a divorce has already occurred without including special needs planning for a disabled child, it is also possible to consider such planning years after a divorce occurs. See J.B. v. W.B. (Bond v. Bond), 215 N.J. 305 (2013) (application by divorced father to pay child support for disabled child into a SNT should be granted where the proponent demonstrates that it is in the child’s best interest to do so).

Choosing among alternatives in this complex area of law requires an examination of various issues, including a parent’s legal duty of support; the emancipation of an adult disabled child; and the child’s receipt of public benefits. By way of example, if a parent has a legal duty to support a disabled child, even beyond the age of majority, then payments in lieu of child support paid to a third-party SNT would violate the parent’s duty of support; accordingly, the possibility exists that these payments to a third-party SNT would jeopardize that child’s eligibility for public benefits.

A discussion of the interplay between a parent’s child support obligation and a disabled child’s public benefits was addressed in the context of a comprehensive examination of autism and divorce by Lawrence R. Jones and David L. Holmes. As the authors explain, a court generally calculates a child support obligation based upon the parents’ incomes, pursuant to the New Jersey Child Support Guidelines set forth in Appendix IX of the New Jersey Court Rules. However, a parent may request that the court disregard the Child Support Guidelines as inapplicable, where “good cause” is shown.

With regard to the issue of a child’s emancipation, a parent’s responsibility to support a disabled child after the age of majority is an issue of state law. Although the laws of New Jersey do not fix an age at which legal emancipation of a child occurs, there is a statutory presumption that emancipation occurs at age 18. That presumption, however, may be rebutted. Courts of New Jersey recognize that child support may continue beyond minority where, on reaching the age of majority, the disabled child is incapable of supporting himself:

Children who are unable to care for themselves because of their minority are no less entitled to the court’s solicitude when they continue to suffer, after they have attained their majority, from a physical or mental disability which continues to render them incapable of self-support. Normal instincts of humanity and plain common sense would seem to dictate that in such cases the statutory obligation of the parent should not automatically terminate at age 21, but should continue until the need no longer exists.

In sum, until emancipation, a parent remains charged with the duty of support.

Consequently, if a duty of support is imposed on the parent, a self-settled (rather than third-party) special needs trust would typically be the appropriate vehicle for those child support payments.

The right to child support is considered the right of the child, rather than the right of the parent, and is based upon an evaluation of the child’s needs. In the unreported Proft decision, for example, the father of the disabled adult child sought an order emancipating the child, and granting reimbursement of past child support payments made, because of the child’s subsequent personal injury settlement. Although the case did not address the public benefits aspect of child support, the court’s observations have ramifications on this issue:

… we are mindful that [the father’s] support obligation … was established by consent. It was not calculated in accordance with the Child Support Guidelines, and may well have been measured by his ability to pay, rather than by the needs of [the child]. As a consequence, even if the [personal injury] settlement were found upon remand to be properly allocated to [child] support, an additional support obligation could remain, depending on the nature and extent of [the child’s] disability, its anticipated duration, and [the child’s] short- and long-term needs.

California practitioners have noted that California courts have not yet addressed whether the existence of an SNT for the child’s benefit would affect a parent’s duty of support, but that one California court allowed consideration of an adult disabled child’s independent income and assets in order to reduce the parent’s child support obligation. However, other states have held that an SNT for the benefit of a child has no impact on a parent’s duty of support.

How a child’s eligibility for public benefits (absent receipt of child support) affects a parent’s responsibility to provide child support to that child is a thorny issue. As one matrimonial law journal opines,

Because SSI is only meant to be supplemental and not substitutionary, a noncustodial parent’s child support obligation should not be impacted if a child receives SSI [in the disabled child’s name]. SSI benefits are “gratuitous contributions from the government” and do not reduce any obligation by either parent…. Along these same lines, a parent cannot refuse to pay child support with the reason that paying would cause the child’s public assistance to end. At least one [Colorado] court has refused that argument, stating that public assistance is paid to substitute the missing parent’s support to provide for a child’s needs. If a parent is no longer missing, it is the parent’s duty to provide for the child, and the substitutionary public assistance has no reason to continue.

See also, Special Needs Child’s Move to Group Home Does Not Alter Father’s Support Obligation, https://attorney.elderlawanswers.com/special-needs-childs-move-to-group-home-does-not-alter-fathers-support-obligation-12770 (citing Minnesota case denying father’s request to terminate child support obligation for adult disabled child based upon child’s relocation to group home covered by county medical assistance, finding that “the primary obligation of support of a child should fall on parents rather than the public”).

Practitioners struggle with the competing issues of a parent’s duty of support, and what the child’s “needs” are when public benefits would otherwise provide for those needs. New Jersey courts have held that, in the case of an adult disabled child, “[t]he child’s’ own resources should first be applied to the cost of his care.” However, in Monmouth County Division of Social Services v. C.R., 316 N.J. Super. 600 (Ch. Div. 1998), in connection with a DYFS placement of a disabled child, the parents entered into a voluntary agreement with DYFS to provide financial support based on the parents’ income and resources. When the child attained the age of 21, the father sought to be retroactively reimbursed for support payments he made to DYFS following the child’s 18th birthday, claiming that he was “no longer legally responsible for the cost of maintenance of [his son] incurred by the Division of Youth and Family Services.” The court denied the request, citing, inter alia, “the basic support obligation of every parent to his child, which transcends any temporary source used to help meet this obligation.” It concluded that the parent’s “limited, but voluntary, financial involvement in meeting his son’s needs is really the affirmation of what was always his fundamental duty, even in the presence of a concurrent role required or permitted of public authorities.”

According to Jones and Holmes, supra,

If the government pays benefits to or for a child (disability, Social Security, etc.), these payments may in some cases reduce a parent’s child support obligation, since the benefits reduce the parents’ costs of raising the child [citing New Jersey Child Support Guidelines, New Jersey Court Rules Appendix IX-A 10(c)]. Receipt of Social Security Disability benefits may reduce child support, while receipt of Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits may not reduce support, since SSI supplements parental income based on financial need.

However, these authors also opine that,

in a case where the [disabled] person is living with neither parent but in another environment such as a group home for developmentally disabled adults, there may be little or no daily out-of-pocket support expenses incurred by either parent, and thus little or no need at that specific time for child support.

Indeed, despite the substantial legal authority supporting payments of child support into an SNT, some practitioners have observed that families rarely seek to have a court order the irrevocable assignment of child support or alimony payments into a trust, “because of the complexity of [the] issue… and the lack of sophistication at the local Social Security office” with this approach:

In our experience, families generally handle the child support/emancipation question in one of two ways: They forego formal support at age 18 and get their child enrolled in all the benefit programs that he or she qualifies for, while making an informal arrangement for supplemental support, or they forego public benefits until age 22 when their child is out of school, and they continue child support payments until then.

Hines, A. and Margolis, H., Divorce in Special Needs Planning, The ElderLaw Report, Volume XXII, Number 5, December 2010.

PROCEDURAL ISSUES

In a Medicaid divorce, a Medicaid application is not made until the Judgment of Divorce is entered. Each party must have separate counsel; if one spouse is incapacitated, the other spouse cannot act as guardian on behalf of the incapacitated spouse in the divorce proceeding. If a divorcing spouse is competent, he or she cannot appear in a divorce proceeding through an agent under a power of attorney. Marsico v. Marsico, 436 N.J. Super. 483 (Ch. Div. 2013).

Because Medicaid will not automatically recognize a property settlement agreement, even if it has been incorporated into a final judgment of divorce, it is important to ask the Court to make specific findings of facts and conclusions of law regarding the fairness of the terms of the property settlement agreement. See H.K. v. DMAHS, supra, 379 N.J. Super. 321 (App. Div. 2005), certif. denied, 185 N.J. 393 (2005). Medicaid should also receive notice of the complaint. Id.; R.S. v. DMAHS, 434 N.J. Super. 250 (App. Div. 2014) (Medicaid agency not bound by court order of support for community spouse entered without notice to Medicaid).

For additional information concerning New Jersey divorce law, visit: https://vanarellilaw.com/family-law-services/#sdpnj

For additional information concerning special needs trusts and disability planning, visit: https://vanarellilaw.com/special-needs-disability-planning/

Categories

- Affordable Care Act

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Arbitration

- Attorney Ethics

- Attorneys Fees

- Beneficiary Designations

- Blog Roundup and Highlights

- Blogs and Blogging

- Care Facilities

- Caregivers

- Cemetery

- Collaborative Family Law

- Conservatorships

- Consumer Fraud

- Contempt

- Contracts

- Defamation

- Developmental Disabilities

- Discovery

- Discrimination Laws

- Doctrine of Probable Intent

- Domestic Violence

- Elder Abuse

- Elder Law

- Elective Share

- End-of-Life Decisions

- Estate Administration

- Estate Litigation

- Estate Planning

- Events

- Family Law

- Fiduciary

- Financial Exploitation of the Elderly

- Funeral

- Future of the Legal Profession

- Geriatric Care Managers

- Governmental or Public Benefit Programs

- Guardianship

- Health Issues

- Housing for the Elderly and Disabled

- In Remembrance

- Insolvent Estates

- Institutional Liens

- Insurance

- Interesting New Cases

- Intestacy

- Law Firm News

- Law Firm Videos

- Law Practice Management / Development

- Lawyers and Lawyering

- Legal Capacity or Competancy

- Legal Malpractice

- Legal Rights of the Disabled

- Liens

- Litigation

- Mediation

- Medicaid Appeals

- Medicaid Applications

- Medicaid Planning

- Annuities

- Care Contracts

- Divorce

- Estate Recovery

- Family Part Non-Dissolution Support Orders

- Gifts

- Life Estates

- Loan repayments

- MMMNA

- Promissory Notes

- Qualified Income Trusts

- Spousal Refusal

- Transfers For Reasons Other Than To Qualify For Medicaid

- Transfers to "Caregiver" Child(ren)

- Transfers to Disabled Adult Children

- Trusts

- Undue Hardship Provision

- Multiple-Party Deposit Account Act

- New Cases

- New Laws

- News Briefs

- Newsletters

- Non-Probate Assets

- Nursing Facility Litigation

- Personal Achievements and Awards

- Personal Injury Lawsuits

- Probate

- Punitive Damages

- Reconsideration

- Retirement Benefits

- Reverse Mortgages

- Section 8 Housing

- Settlement of Litigation

- Social Media

- Special Education

- Special Needs Planning

- Surrogate Decision-Making

- Taxation

- Technology

- Texting

- Top Ten

- Trials

- Trustees

- Uncategorized

- Veterans Benefits

- Web Sites and the Internet

- Webinar

- Writing Intended To Be A Will

Vanarelli & Li, LLC on Social Media